Scott Liddicoat

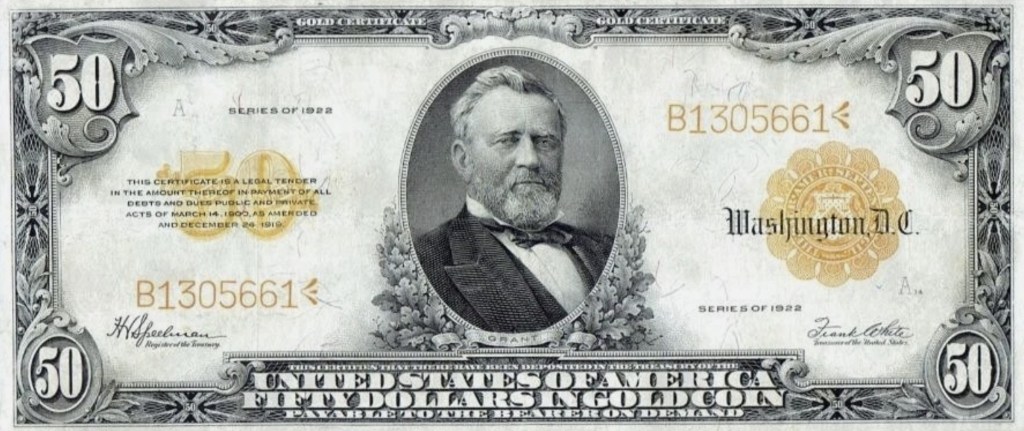

Several times in my teaching career I’ve had the privilege of talking with young students about money. For reasons that will be clear in a moment, I always took gold coins along with me. I also took silver coins, and gold and silver certificates, along with a selection of what passes for money today.

Each time I started my presentation with three words on a chalkboard:

I asked my student audience which of the three it was important to have the most of. [Before going further, what is your choice?]

Many students replied that it’s the most important to have a big income. After all, it’s expensive to live and you need lots of money every month to pay the bills. A few kids would say that wealth is the most important. Often they weren’t sure why, but the word seemed to inspire their respect. Most of my student audience usually said having lots of money was the most important.

At that point, since I was the guest speaker, they wanted to know what I had to say. I told them that I really, really liked money—lots of money. But it was far more important for me to have big wealth.

Since most young people aren’t really sure what wealth is, I gave them a simple definition. But it’s been a critically important distinction for me. My wealth is what I’d have if I sold everything I owned and used that money to pay off everything I owed. What money I had left over would be an expression of my wealth, and I want that to be a really big number.

Most people call it their net worth, and I told students that.

“But what you’d have left over is money!” an observant student might say. No disagreement there. But then I’d go on to say that what I think of as money is probably very different from what they think of as money. Money is not just something that people use to pay for things with, or to judge value or worth with. Real money is something that is, by itself, valuable.

An easy way to think about this is to imagine having a metal shredding machine. After running today’s coins through the machine, you’d have only a few cents of cheap, base metals to dispose of. But if you ran gold coins through the shredder, you’d spend the next half hour sweeping up every last particle of gold dust for safekeeping.

Lots of gold shavings are just as valuable as the gold coins. Gold is, by itself, valuable.

Another easy way to think about it is to place a fifty dollar bill on the counter next to a one ounce, fifty dollar American Eagle gold coin. Given the choice, which would you rather have? My students knew the answer to that question by instinct without any explanation. The paper and ink materials in the fifty dollar paper bill don’t begin to measure up in value to the gold in the coin.

The gold, by itself, is valuable.

Gathering students around a table, I’d ask them to get out some of their money to look at. As I got out my money, students were captivated. Right away they saw the difference between their coins that looked like silver, and mine that were real silver and gold. They recognized the big difference between their paper dollar Federal Reserve Notes and my older, paper Gold and Silver Certificates.

“Back in the day” I would have been able to turn my Certificates in for real gold and silver at any bank. My money is valuable.

Of course, I can no longer get gold or silver with certificates of any kind at a bank. But at least the banks provide me with a safe place to store real silver and gold money.

But not that long ago, people always used silver or gold for money. Or they used “as good as gold” Certificates.

The silver or gold they used to buy things was equally as valuable as the item they were purchasing. They were exchanging valuable money for something just as valuable—not paper and ink for something valuable. Young students get this when they see real gold and silver money. And they understand it easily because they have yet to be tamed by the economic and investment “experts.”

My student audience was usually interested to hear me say that it took me a majority of my life to figure out what money really is (or what it should be, even today). That it wasn’t possible for me to become wealthy until I knew what money was. But once I figured it out, becoming wealthy wasn’t very hard, even with a modest income.

Before finishing, I’d remind my students that money is important. But understanding real money and wealth was way more important. Also, genuine wealth was far, far more important than the kind of wealth I’d been talking with them about. Doing good deeds first with your money provides for true, authentic wealth.

Then I’d tell them there are two steps they needed to take to begin their understanding of money and wealth. I could provide them with only one of the two. First they must hold a gold coin in their hand. I let them pass a gold ounce from one to another in the open palm of their hand (telling them if they ever closed their hand around it I’d tackle them!). They were fascinated by its weight (density) and beauty, and again, they just get it.

Then I tell them the second step is for them to buy and keep a gold coin—even a small one—for themselves.

The purchase of gold brings together everything that went into my classroom presentation—fascination, an understanding of value, the definition of money, and a special perspective on money and wealth. If you’ve purchased gold before, you know exactly what I mean. Buying gold is special every time.

If you haven’t purchased gold before, I invite you to buy a one ounce gold coin soon. It’s exciting! You’ll be taking a critical step toward real wealth and real financial security.

Most of the words you’ve read formed the first version of this writing. It was published years ago by Russ Schmidt in his EASY Economics and Personal Finances. Russ (1776) was extraordinary at making everything about money and investing easy to understand. More than that he was an extraordinary friend and patriot. I wish for any of you reading this that you may find and treasure such good people in your life.